Rachal BradleySalty water, what of salty water? (2007)Text

Life began in fluid.1

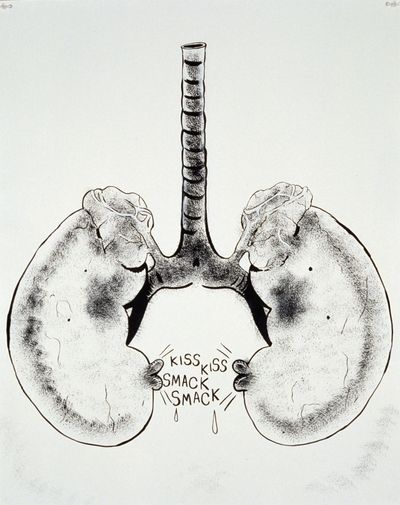

Our kidneys go through three stages of development. As blood cleaning machines they give away the story of human evolution from sea creatures to land bodies2.

Life still begins in fluid, in vivo, is in fluid.

Vicious Cycles

In April 2008 my lymph nodes became infected with a virus, perhaps they were already infected, but this was the point that a young female doctor, younger than me, announced this was the probable problem. One symptom of the virus was a heightened susceptibility to booze. The virus inflames the liver and kidneys, making it more difficult to process alcohol and accelerating its intoxicating effect on the body. I was in the shitty phase of a relationship that would never succeed. I had thought I was simply getting old. In fact my lymph nodes were not able to clean the toxins out of my body as they mobilized to fight a battle on another front. These clagged, corporeal filters of immunity and circulation slowed me down, made me weak, thin and prone to being drunk too quickly. I wanted to eat but the hike to the kitchen and the effort of cooking barely equalled the energy I would expend in the task. Decisions boiled down to the simple formula of input versus output. Which mostly boiled down to soup. I became more dependent on Shitty Relationship for physical nourishment and recuperation. I was living off state benefits of £45 per week (approx), unable and unfit to work for money. At my lowest point in weight, cash and libido I retreated to the house I grew up in to begin recovery again.

Life began in fluid.

I grew up by the sea. I saw it everyday on the way to school from 1983 to 1997. It was the background. A monolith of expanse. It felt like neither potential nor inspiration. I could never understand the poetic versions I had read about in literature. My sea resembled a desert, a dearth of oily brown.

I was born in the year Margaret Thatcher was elected to power. 18 years later, Labour, New Labour, were elected to government. The same year, a legal adult, I left the town3 I grew up in, to enter another world at the beginning of what felt like a propitious, changing landscape. A tide turning for the better, a new party of the left, fit for purpose, fit to govern, making everyone fitter, fit more.

In 1997, I would be the last year of students to be paid for by the government under a universal right to further education policy. The final wave. The same policy had delivered my father gratis into university, 25 years before. This was one part of his generous baby-boomer package received as matter of right in the glow of post-war Britain. In the pre-Millennium glow of New Labour this universal right to free education was to be severed in the first Judas kiss of legislative changes by the New government.

Now I look at photographs taken during my illness recovery, and I scarcely recognise the emaciated frame under a red cagoule on the beach; a little bony tent bearing a smile, dwarfed by the lurching smudge of the sea. Was it a deliberate conceit to wear active gear throughout this period of ultimate rest? It’s clear now that my eyes colluded with the Virus to distort my reflection – presenting a hopeful view back to me. Narcissism has its benefits?

Why had I hated this town by the sea so much growing-up? Does the act of writing require a moment of revelation? Is there always a moment where things become clear for what they are? When the toxins have finally been flushed out.

Bed Ship

Droopy from illness I read everything possible before dropping off. Between sleeps I was watching films, and researching writers and artists who preferred or were compelled by illness to be prostrate4. As I was trying to find justification for my state of being (why had my body done this to me?) I came across the Communard and anarchist Louise Michel’s description of her time incarcerated in the brutal Saint Lazare prison, “I‘ve found a happiness in prison that I never knew when I was free.”5

I spent more time on a bed and surfing the Net than ever before6. It became a sort of oneiric productive, non-productive state, bobbing on fragments of information here and there in a personal sea of anecdotal knowledge, dredged in from this source, this state of being. It was a nascent, personal sea, forming through horizontality. There’s a sort of masterlessness that occurs within the horizontal viewpoint. The view from a prostrate position looking across onto the material world is a surrender of the upright vantage point of man, a denial of the careful and chaotic evolutionary processes formed through thousands of years of natural selection. A defiance of Man’s body-ego-centric perspective. The passive body at full strength7. My body had decided to make this radical act not my mind and not through pro-choice, rather through the luxury of disease, through the persisting repetition of the Virus.

-

This title of this essay is derived from the title of an exhibition named Salty Water/What of Salty Water, an installation by artists Paulina Olowska and Bonnie Camplin at Portikus, Frankfurt am Main, Germany, 05/25/07 – 07/01/07. ↩

-

Known as ‘recapitulation theory’ - In utero, we develop three separate kidneys in succession, absorbing the first two before we wind up with the embryonic kidney that will become our adult kidney. The first two of these reprise embryonic kidneys of ancestral forms, and in the proper evolutionary order, namely primitive aquatic vertebrates (lampreys and hagfish), semi-aquatic vertebrates (fish and amphibians), and finally the Metanephric kidney the final adult kidney of reptiles, birds and mammals. ↩

-

Also the host town of the Conservative Party conference for alternate years between from 1993-2007. ↩

-

Of which there are many, to name drop a few, M.Proust, H.Matisse, G.Orwell, Colette, M.Twain and E.Wharton, V.Nabokov and T.Capote. ↩

-

‘A visit to Louise Michel’, Paul Lafargue, Le Socialiste, September 26, 1885. ↩

-

I received my first email address 11 years earlier in 1997 as a student within the University of Bristol network. ↩

-

Heidegger (in Being and Time) and Husserl (in Outset from Significations of the Word Logos, Speaking, Thinking, What is Thought) both discuss the philosophical term logos, an antecedent of the more commonplace term logic, meaning reason itself. Tracing the term to its Greek derivative of legein, it seems more than a poetic coincidence to unearth the literal meaning of this as “to lay down and lay before” (Heidegger) or “to lay together” (Husserl). Heidegger and Husserl think through the original meaning of legein to get to some understanding of logic and its centric position within western thought through language and speech. Their arguments are too lengthy to jump into here, but what always intrigued me is the visual image of reason as something spatial or occupying a plane. Heidegger and Husserl focus on the act of un-concealing something through the action of laying out, but do not mention the quite literal implicit horizontality in this action. ↩

It only rains where it is wet or piove sul bagnato

By the time I am back in The Town by the Sea I Grew Up In, the world’s stock markets have reached their own crisis point. 00:01 22 February 2008, Northern Rock bank is nationalised when it fails to replace money market funding drained from its coffers following toxic investments brought to bear by the credit crisis of 2007. Northern Rock was the first bank to be ‘run’ on in 150 years of British banking. It’s such a precise phrase – certain economic and legal terms are at once visual, literal and abstract, (overwhelming the consequences therein) they meld historic symbology, emotion and action with the dexterity so particular to the gaps opened up by the morphing of language. All those people running into the bank grabbing their bags of cash, notes flying everywhere, panic, admin, chaos. Glitches in the system, systems overloading virulence, pathologically excreting and sweating numbers, value and assets. Since the Seventies money has moved in waterfalls of digits on a screen. But the term ‘run’ is preserved to remind us that the contradictions of old have never been resolved only superimposed with newer ones. But with its continued use there is suggestion, a hint of a manic, unbounded, physical recuperation of these financial systems by people in common. “Bre ke ke kex, koax, koax” chants the Chorus in The Frogs, “Bre ke ke kex, koax, koax”.1

Venice (sinking economies)

Shitty Relationship and I both knew but we hadn’t quite laid it out. Although unconcealed it was not yet visible as a declaration to each other. The realisation was between us, un-landed, still needing to be tethered in order to become information. It was pre-digestion. The acceptance of symptoms is part of the cure but you have to be willing to make the move and I was in a vague and slack season. I would have given my consent had I felt strong enough or passive enough.

Nora Barnacle complained heavily of James Joyce in letters to her sister. Particularly vexed were her criticism of his writing as obscure and lacking sense. His whimsy in financial matters seems to have magnified further her frustrations with him. In 1931 she became his wife. Shitty Relationship and I were sinking in direct correlation to my libido. He felt sorry for me but couldn’t find the kindness to articulate the real. In this state of being, vague and slack, I was at once repossessed – in this affliction, this emotional austerity, I could just be. And although I could see this thing slipping away, it was all part of the flush out.

Unconditional Authority

In 2004 the explicit, rousingly coprological letter penned by Joyce to his wife Nora was sold by Sothebys auction house for £240,800. While apart these letters were flights for the graphic, idiosyncratic sexual intimacy between Nora and James. Fuckbird and Jim lay out with remarkable poetry the refinement of their sexual complicity. Brought about by Joyce’s direct sensory and literal habitation of sexual language, the brown mark he encourages his wife to leave in her starched drawers, evokes pre-linguistic urges of childhood weirdness and investigation. Urges of an unbound sophistication, yet to be tethered to culture, morality and conformity.2

Ten years following the Joyce/ Barnacle letter sale, the site for the spectacular, new Tate Modern was selected. The redundant power station on the South Bank had its machinery and innards gutted two years later by architects Herzog & De Meuron as part of the extensive re-fit for the capital’s premier contemporary art gallery.3 Numerous pumps and pistons were removed, walkways installed, walls whitened. And so in 2013, year on year since the New Labour Millennium the Tate Modern has brought £100 million in revenue to London. It is perhaps one of the most successful accounts of what Franco ‘Bifo’ Berardi describes as the ‘semio-capitalisation’4 of culture in the UK. The Tate glows radioactive neon each night doubled as image in the river Thames. What were once spurts and splurges of criticality, expression, intimacy, emotion, formal investigation is now a sea, nay ocean of Culture. Given this inflated and swollen value of culture in capital terms how can we even begin to see art anymore?

The Real

Photography is always born from fluid. Literally meaning image made of light, the wetness of the process was always more intriguing to me. As an art student I would hole up in the dark for hours, agitating and washing out the image from chemical cocktails, sublime in solitary and sensory confinement. A state of being not unlike the vague and slack season. Days before I leave to return to London, I find a photograph I took as a child. It’s a self-portrait, maybe I’m about 7. Dressed in a tracksuit, my hair is speckled by summer sunlight against stodgy green velvet drapes. I’m posed ready for action, provoked and open holding a cigarette lighter in the shape of a gun.

Land Creature

2013 and I still have no money, although impressed by being less in debt I am also more healthy.

-

The Frogs, by Aristophanes first presented in 405BC. This footnote is too limited to exalt the unnerving pertinence of this comedy. Suffice is an overwhelming recommendation to read it urgently. ↩

-

The Joyce/Barnacle letters were first published in 1975 as part of Richard Ellman’s Select Joyce Letters, now out of print, and have been treated with trepidation by the Joyce estate. Some have been transcribed and can be read on the following website https://adoxoblog.wordpress.com/2011/02/25/fμckbird-and-jim-james-joyces-letters-to-nora-barnacle/ ↩

-

The Tate is particular to not deploy the term museum at any point in self-descriptive literature either printed or web-based. ↩

-

“Semiocapital is what he calls the capitalist subsumption of the general intellect, the putting-to-work of collective intelligence, and the financialization of our sociality. Facebook et al. As capital has colonized more and more of our mental space, it has filled our heads with flashing advertisements and short videos of cats, more or less driving everyone insane. In short the “vicious subjugation of life, wealth, and pleasure to the financial abstraction of semiocapital.” Franco Berardi, The Future After the End of the Economy,” @ e-flux, (Online: August 2011). ↩

Biography

Rachal Bradley (born 1979) is a British artist.